As the struggles of decolonization unfold at the level of nation-states, stories about the colonial past are often told from a perspective of a victim. Such flattening narratives deprive individuals the agency to form an autonomous view of their history, leading to a reduced sensibility of geographical, psychological, and cultural complexities, even cultivating a polarising nationalism. With that considered, this essay is born from a necessity to understand how contemporary artists from Hong Kong and Taiwan have been using the intricate intertwining of the known and the unknown to suspend hostile reflexes towards colonial history, and to reframe the fiction bred by unverified historical details for a more nuanced identity.

“Archival impulse,” a term coined by the American art historian Hal Foster, was originally used to describe an artist’s will to overcome a failure in cultural memory through archival footage. What Foster has not noted, but has been widely shared by artists engaging with the legacies of colonialism, is that beyond the pursuit for historical accuracy, there is an obsession with the imaginative potential energized by the voids in archival records. Such an impetus is at the heart of the immersive installation Bright Light Has Much the Same Effect as Ice (2012), created by Hong Kong artist Leung Chi Wo. Coming to terms with the absence of photographic proof of the scenic snow on January 18, 1893, the coldest day recorded in the history of Hong Kong, Leung managed to reenact the mythical occurrence of snow through a choreographed series of fragmental clues and inquisitive gazes.

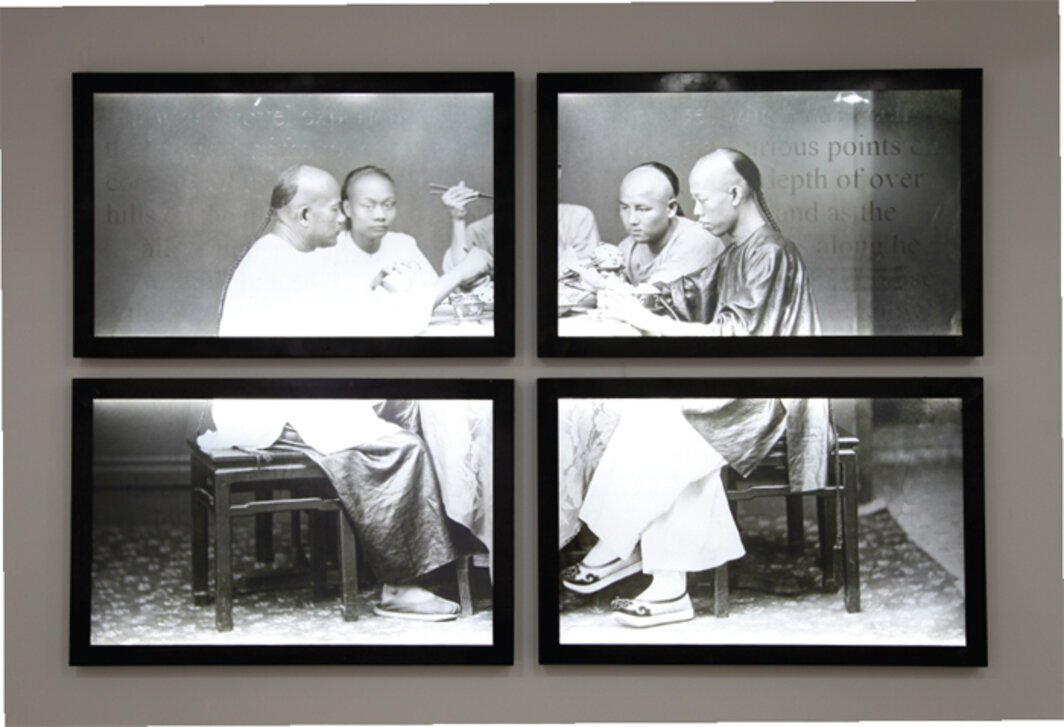

Mimicking the mechanism of the click of a camera button, a freezing silver coin minted in 1893 was turned into the control button which prompted when the journalistic texts engraved on plexiglass could be seen. Beneath the plexiglass, there is a studio portrait of a staged dinner scene of the Qing Dynasty. This seemingly unassociated portrait was actually produced by a photographer who had been mentioned in a written report in The China Mail (a local newspaper) for having taken a number of shots of the white-capped hills on that day. While four of the Chinese sitters in this portrait kept their gazes down, one looked at the camera in a way that suggest he was exchanging gaze with the photographer who likely witnessed the snow scene.

Since the year 1893 situates the photograph in the British colonial period, the sitter’s gaze toward the camera can be easily interpreted as a violation of the colonial gaze embedded in the 19th century photographs of Chinese vernacular scenes. However, by drawing an implicit association between the sight of the snow scene, the photographer, the sitter, and today’s viewers, Leung fosters a visceral connection with the history, one that has been suppressed by the one-sided postcolonial lens. Meanwhile, Leung proposes that we reflect on our own gaze, a primary documentation tool, and its potential to traverse the undercurrent of time to reach into the past and the future.

The Narrow Road to the Deep Sea (2019), a pseudo documentary by Hong Kong artist Lee Kai Chung, similarly explores a personal relationship to unverified but truthful accounts of the colonial past. During the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, thousands of refugees died from bacteriological tests. However, the details of the notorious crime are rarely mentioned by official documents. Mixing bone-chilling facts with fictitious vignettes inspired by testimonies gleaned from Japanese veterans, survivors, and their descendants, the work deceives the audience with a progressive purpose: the viewers are supposed to notice the very conceit, fictional quality, and untrustworthiness of the narrative on their own.

Lee concluded the piece with a performance in Toyama Park, the former site of a military medical school at which many medically mutilated bodies were excavated after the war. There, he dug a hole in the ground, not with the intent to excavate, but to reenact the conflicted psychological status of different participating parties facing the wartime culture of violence. “Through hours of physical labour, I felt the buried consciousness of the living, the dead and the evil,” says Lee.

While Lee’s attraction to the abject facet of humanity lurking in colonial trauma reveals his anxiety towards the ongoing political split in Hong Kong, the Taiwanese artist Chen Chieh-jen explores what foreshadowed the colonial violence, and how it residually impacted today’s capitalist guilt in a film titled Lingchi—Echoes of a Historical Photograph (2002).

Starting in the nineteenth century, the ritual of lingchi (death by a thousand cuts) was photographed by colonial soldiers as pseudo-ethnographic documents and distributed in Europe through postcards. Although European powers have been historically criticized for using the barbarism embedded in images of lingchi to legitimize their colonization of China, Chen believes it is necessary to reclaim the witnessing and interpretation of the severe and unrelenting practice in Chinese history.

Finding it hard to determine where violence originated, Chen is more concerned with how contagious violence can be. Having unemployed factory workers and other members of marginalized communities take on the roles of the condemned felon, the executioner, the European photographer, and Chinese onlookers from the Qing Dynasty, Chen invited these performers to confront the cruelty attributed to their culture which had since been blurred through the decolonizing process.

The cycling of violence moves from external acts to internalized and institutionalized malice, from the visible brutality in the past to the hidden violence in the current global economic structure. In the middle section of the video, as the camera pans across the wounds cut into the victim’s torso, a series of documentary photographs are shown from inside: the Old Summer Palace in Peking, which was destroyed by European invaders in the 1860s; a prison in Taiwan, which was used for political prisoners during the martial law period from 1949 to 1987; and a clothing factory, which was closed down after a transnational corporation transferred its processing plant from Taiwan to mainland China for cheaper labor. The sequence of images not only teases out how historical crimes evolved, but also problematizes today's use of citizenship as rallying points in mapping terrains of struggle.

The cultural memories of colonialism have been integrated into the political awareness of the above artists through unspoken mechanisms of intergenerational transmission. By reimagining and reenacting complex myths about the past, their artworks cultivate a collective sensibility to historical narratives, and inspire a cross-border solidarity against state-machinery, as well as neoliberal forms of social engineering.